In Search of Steve Ditko

May 20, 2012 at 10:52 PM by Dr. Drang

The release of The Avengers has brought out the old grievances. Jack Kirby partisans—many, if not most, of whom are too young to have ever bought a Kirby comic except as a reprint—are shaking the mothballs out of arguments that started four decades ago and giving them a fresh airing.

This article by Alex Pappademas at Grantland, which I read after following a link from Merlin on the latest Back to Work,

I am appalled by the injustice but not surprised by it. The comic book industry has had the same sensitivity to the rights of artists that the music industry has. Extracting fair payment from them can only be done through the civil court system, and they’re a step ahead of you there, too. Pappademas rightly points out that Stan got a better deal than Jack because Stan was part of management. And even Stan had to sue to get the payment he was due by contract.

So I’m all for reminding people that Kirby got screwed, but I won’t go so far as to say that he was the primary creator of the Fantastic Four, Thor, Iron Man, the X-Men, and so on. So much of the life of those characters came from the dialog: the corny, post-war New Yorky chatter that is pure Stan Lee.

There’s no question that during the height of the Silver Age, Stan got—and took—more credit than he deserved. Pappademas rightly portrays Stan as a self-aggrandizing spotlight-grabber, but that’s hardly incisive or original reporting. Part of Stan’s charm is that both you and he are in on the joke; Stan is his own greatest creation.

In his later years, consumed by bitterness, Jack said that Stan never created anything without him, and that was the proof that Jack had done all the work. But that’s hard to swallow. First, Jack’s solo work was, to put it mildly, somewhat less enduring than his work with Stan.

No, Spider-Man has his own story of an artist that didn’t get the credit he deserved. It was a story I didn’t know much about until I watched Jonathan Ross’s 2007 BBC documentary In Search of Steve Ditko a few nights ago.

I knew the basics: Steve Ditko was the first artist for both Spider-Man and Dr. Strange, and he had a Kirbyesque feud with Stan over creator credits for Spidey. He left Marvel abruptly in the mid-60s and sort of dropped off the face of the Earth.

Ross’s documentary fills in the details—the details that are known, anyway, which aren’t many. Ditko doesn’t believe in giving interviews, doesn’t seem to have any friends, and never spoke much to his coworkers back when he had coworkers. There’s just the work, an amazingly uneven assortment of odd comics about odd characters, especially after he left Marvel.

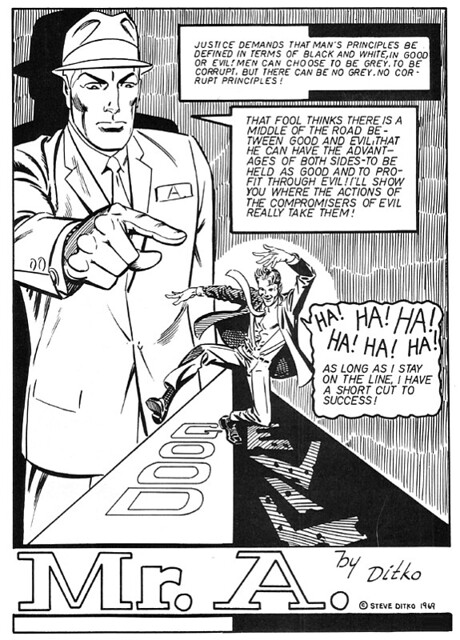

The most famous of Ditko’s post-Marvel creations was Mr. A, not so much a superhero as a stand-in for Ditko’s version of Ayn Rand’s Objectivism. And Mr. A’s fame is due less to Ditko’s efforts than to his being the model for Rorschach in The Watchmen.

Alan Moore, by the way, is a big fan of Ditko’s and appears prominently in the Ross documentary, telling an ironically funny story about Ditko’s reaction to Rorschach.

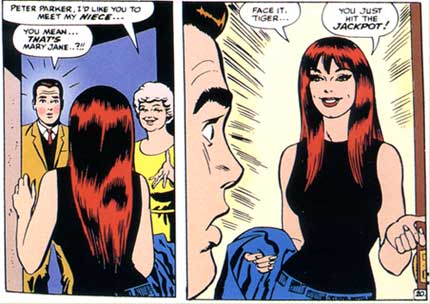

John Romita, who took over as Spider-Man’s artist when Ditko left, is also in the documentary and is both generous to Ditko and self-deprecating, saying that he couldn’t match Ditko’s vision of the character and drew Peter Parker as too handsome. This fits in well with the theme of the documentary, but I couldn’t disagree more. Yes, Romita made Peter look good, but the look wasn’t heroic in the Kirby vein. It was handsome in the style of romance comics, which Romita had worked on for several years at DC. This was the perfect look for a comic book that was, under the superhero mask, a full-on soap opera. And, be honest, would you really want Ditko doing Mary Jane’s entrance?

(I’m thoroughly unobjective on this. Romita is far and away my favorite Marvel artist. My greatest regret is that my few years of comic book collecting started just after his run with Spider-Man. I had to supplement the tepid Ross Andru in the current books with Romita reprints in Marvel Tales.)

The most revealing interview in the documentary is with Stan Lee. Stan has said, publicly, that he considers Ditko to be the co-creator of Spider-Man, but Ross—perhaps because he knows what makes a fellow egomaniac tick—gets Stan to admit that although he’s said that to appease Ditko, he still sees himself as the creator of Spider-Man. “I really think the guy who dreams the thing up created it. You dream it up, and then you give to anybody to draw it.”

I’ve read lots of articles and autobiographical sketches by writers, science fiction writers in particular, and I don’t remember a single one of them saying anything like that. On the contrary, they usually say that the dumbest question they’re asked is “Where do you get your ideas?” Ideas, they say, are easy. Everyone has them. Working on those ideas and turning them into stories is what counts.

So is Stan just some gasbag who said “Let’s make a superhero called Spider-Man”? No. In another part of the documentary, they go through argument Lee and Ditko had over the identity of the Green Goblin. Stan wanted him to be someone already known to the readers; Ditko insisted he should be a new character entirely. Stan, of course, had his way, and the Green Goblin was revealed to be Norman Osborn, the father of Peter’s best friend. No less an authority on good storytelling than Neil Gaiman weighs in on this decision: “Obviously, Stan was right. Stan’s instincts as a storyteller were absolutely spot-on.”

If Neil Gaiman thinks Stan was a storyteller, that’s good enough for me.

In Search of Steve Ditko has a wonderful ending that I won’t spoil for you except to say that it fits in perfectly with everything that’s gone before.

If you’re a serious comic book fan, you’ve already seen In Search of Steve Ditko. It is, after all, five years old. But if your interest in Silver Age comics is more casual and you haven’t seen it, go stream it now. You’ll enjoy the hour you spend with Jonathan Ross and his guests.