Toolbox projects

January 23, 2011 at 8:16 AM by Dr. Drang

I’ve been hoarding podcasts recently. I have a couple of long, solo car rides coming up next week, and I want to keep myself entertained with In Our Time, The Talk Show, The Bugle, and others. I was going to save Merlin Mann and Dan Benjamin’s new Back to Work for the ride, too, but when I learned I was mentioned in it, I couldn’t wait.

It was a good show, of course, because Merlin is always fun, even when he’s haranguing us about what slackers we are. More interesting, I thought, was Dan’s persona on the show. If you listen to Dan’s other 5by5 interview shows, you know he tends to keep his light under a bushel, always keeping the attention on the person he’s interviewing, often asking questions he certainly knows the answer to just to get the interviewee to talk more. Merlin turned the tables on him, though, and we ended up hearing the Dan we’ve been reading on Hivelogic.

So, it was a good podcast, and I look forward to seeing what they do with it. But what I really want to talk about today is Fine Woodworking.

My dad was quite a good amateur woodworker. In his teens, he’d worked in a cabinetmaking shop and was probably happier there than in his later engineering jobs. He and my mom moved to a new house shortly after he retired, and he spent the first few years building and installing all its cabinets.

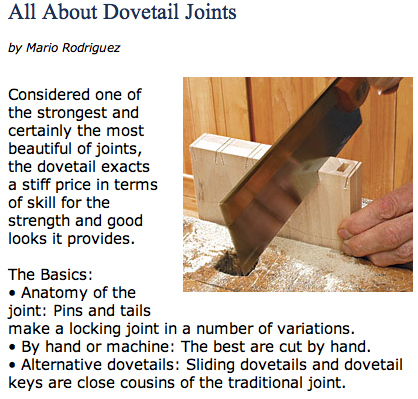

Dad kept a big stack of Fine Woodworking magazines, and I used to thumb through them when I visited. Fine Woodworking was pitched toward professional woodworkers and high end amateurs and most of its articles were about techniques: various ways to make joints, choosing and applying finishes for different effects, keeping your chisels sharp, that sort of thing.

Probably the second most common type of article was the project article. Written by a woodworker, the common outline of a project article was:

- Here’s a piece that I made.

- Here’s how I made it.

- Here are the aesthetic and economic reasons I made it that way.

Although I’m not a woodworker, these articles always interested me because they blended the how and the why. You learned why the drawer fronts were made of cherry and why the pulls were nickel-plated steel instead of wrought iron. A Popular Mechanics article about building a doghouse from a half-sheet of plywood would never do that.

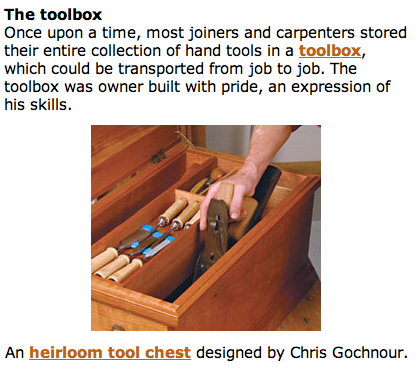

I did notice, though, a recurring theme in these project articles. While many of the projects were professional pieces done on commission, and many were labors of love, like an anniversary gift for the woodworker’s in-laws, most of them were toolboxes.

Or tool cabinets, or workbenches. The point is, the most common woodworking projects were woodworking projects about woodworking. Which seems a little recursive, if not downright masturbatory.

Which brings me around to Back to Work again. While I love the podcast itself, I’m not keen on the title, mainly because of the word “work” and the usual connotations it carries. If we ask ourselves whether the guy who built himself a great toolbox was working when he made it we’d have to say no. He didn’t make any money from it, nor was it a loss leader to promote his business, so maybe he should’ve been doing something else.

But if we ask ourselves whether it was worthwhile, we’d probably give a different answer. The woodworker certainly had a fun and relaxing time building his toolbox, and he ended up with something that gives him pleasure—both the direct pleasure of having built something that’s attractive and useful, and the indirect pleasure that comes from having others admire it. And he developed or honed skills that he will use in his work.

So the toolbox was definitely worthwhile, even though it wasn’t work.

In the same way, knowledge workers don’t always have to be doing work to be doing something worthwhile. The little scripts I write and present here have never made me a dime, and they’re certainly not an advertisement for my company, but they amuse me. They eliminate some of the dull repetitiveness of daily computer work, and let me see myself as the master of my computer rather than its slave. They’re my toolbox projects.

And, luckily, the skills I’ve developed in my little toolbox projects can be translated to my “real” work. As an example, I was recently sent a finite element model of a structure—a large text file describing the structure’s geometery, material properties, and loading. My job is to reanalyze the structure using a new approach, and the first step is to extract the pertinent information from that big text file. When I bid the job, I knew that first step would go quickly because of all the experience I have at filtering text files through Perl and Python scripts.

I’ll end by saying that I don’t think Merlin and Dan have the restrictive view of “work” that I’ve used here, so they’re idea of Back to Work is broader than mine. Merlin’s always said that he sees his mission as helping people find ways to accomplish what they want. I’d add that accomplishments don’t have to be associated with work.